Growing wild in the hilly and mountainous regions of Bhutan, China, India and Nepal, the Himalayan nettle (Girardinia diversifolia), known in Nepali as Allo, is a valuable raw material that can be processed into a fibre stronger than jute. The thread is used to make a range of products including bags, clothing and accessories, while other parts of the plant can be used to prepare traditional medicines to treat various diseases and ailments.

Allo is just one example of high-value niche mountain products hailing from the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH), which includes all of Bhutan and Nepal, and the mountainous parts of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, India, Myanmar, and Pakistan. Other high-value products from the mountain regions include pashmina shawls, handmade paper, Himalayan honey, tea, coffee and spices, among many others.

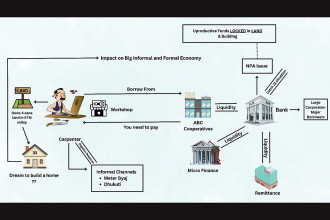

These products, enriched by traditional knowhow, skills and Indigenous knowledge systems, are highly sought after in many high-end urban and international markets. Despite this, and its wealth of biodiversity and indigenous knowledge systems, the HKH is home to some of the world’s poorest people. There is a need to unlock the entrepreneurial potential in our mountains, and for businesses to support farmers and artisans in our mountain communities – ultimately to improve their lives and livelihoods. For this to happen, a functional ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’ must be established, along with an ‘enabling environment’ which would include well-functioning institutions, a stable macroenvironment and high-quality infrastructure.

Entrepreneurial ecosystems are composed of interdependent sets of actors and institutions. First coined in a Harvard Business Review article in the 1990s, the phrase has come to identify a system where entrepreneurs are placed at the centre and the contexts that either enable or constrain entrepreneurship are equally emphasised – echoing how elements in a natural ecosystem interrelate.

The Netherlands, known for its mature entrepreneurial ecosystems, offers some effective lessons in unlocking entrepreneurial potential.

Two organisations based in the Netherlands united with a group of experts from government institutions in the HKH region, and the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), based in Nepal, for an exchange programme on entrepreneurial ecosystem cross-learning and collaboration. The two Netherlands-based organisations were PUM, a volunteer organisation whose aim is to enable the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries and emerging markets, and WorldStartup which focuses on inclusive and regenerative global economy for a sustainable future.

The entrepreneurial ecosystem in which they operate broadly comprises four core components – culture, demand, institutions and infrastructure – and six sub-components – finance, talent, intermediaries, new knowledge, networks and leadership. This ecosystem, and a number of inter-connected elements, have resulted in a phenomenon known as the ‘Dutch Entrepreneurship Miracle’ – referring to the fact that the rate of entrepreneurship (i.e., the number of entrepreneurial ventures) more than doubled between 2002 and 2012 in the Netherlands. Here we discuss how these elements can be contextualised to unlock entrepreneurship opportunities in the HKH.

Formal institutions and policy support

The Dutch government is committed to building an entrepreneurial climate by creating the right conditions for business to thrive, especially for key areas including agri-based businesses, water and energy. It has enabled cooperation between research institutes and businesses, created a competitive business climate by eliminating hurdles, clearer regulations, and business-friendly fiscal policy. The government has positioned the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy as the central access point for government information and services in the areas of innovation, exports and financing.

A number of initiatives, formal institutions and investment funds backed by the Dutch government play a crucial role in leveraging resources and networks to support aspiring entrepreneurs to start their venture, apply for entrepreneurship grants and loans, help them enrol in business incubation hubs and provide mentorship facilities. They also support challenge funds, hackathons, and other events and sponsorships.

Business incubation centres

It is no coincidence that some of the numerous business incubation centres in the Netherlands are located on university premises, partially funded by the government. For example, Wageningen University and Research (WUR), has a startup incubator facility on campus called ‘StartHub Wageningen’, which develops the entrepreneurial competencies of students and helps develop their ideas into business models. A spirit of openness to innovation and extending services to international students has played a large part in the Netherlands hosting several innovative businesses and startups.

One example is aQysta, whose CEO and one of three founders, Pratap Thapa, is originally from a small village in Nepal, where the farming community had difficulty accessing water during the dry season. After receiving a scholarship from Delft University for Technology in the Netherlands, Pratap co-designed the ‘Barsha Pump’ with fellow founders – a water wheel-propelled pump that uses the flow of rivers to pump water for irrigation at a low energy cost, without the use of electricity or fuel.

Tapping into demand

A growing number of consumers are becoming aware of the negative environmental impacts of mass production and over consumption. As the demand for environmentally friendly products increases, the trend suggests that big business will begin to make efforts to become more environmentally sensitive and responsible with their production and waste management; the new generation of entrepreneurs in particular is keen to collaborate with sustainable businesses.

To bridge this gap between demand from conscious consumers and supply from traditional suppliers, entrepreneurs need to step in with new and innovative solutions. One example is from a group of Dutch students, who tapped into a growing demand for nature-based detergents and soaps, after realising that a segment of consumers in the Netherlands did not wish to use chemical-based detergents. The students contacted producers in Nepal who were making natural soap from the shells of the Sapindus mukorossi fruit, commonly known as Indian soapberry, washnut, or ritha in Nepal. They founded the company ‘Soaply’ – selling a line of detergents, handwash and soaps made from natural ingredients. This start-up is an example of an unexplored nature-based business that has growing demand in the market.

Learning from the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, there is a strong belief in the concept of the ‘triple helix model of innovation’, which refers to constant interactions between academia, industry, and government. Leydesdorff’s quadruple helix model takes this a step further, emphasising social responsibility and the involvement of citizens in research and development. Following these models has fostered a strong entrepreneurship spirit and a nurturing foundation for entrepreneurship to thrive.

Start-up community culture

A salient feature of the Dutch entrepreneurial ecosystem is the ‘start-up community’ where universities, governments and investors can be ‘enablers’ of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. For instance, the multinational consumer goods company, Unilever, has established a state-of-the art ‘Foods Innovation Centre’ at Wageningen University, where students develop innovations on sustainable foods. Enablers have created a local culture that is conducive to start-ups, with social values and organisational norms in favour of entrepreneurial risk taking.

Other emerging concepts include ‘zebra’ start-ups which aim to alleviate social, environmental or medical challenges while tending to their own profitability; stewardship, post-growth, social entrepreneurship and circular economy that are attracting many sustainable businesses and young entrepreneurs.

Youth and our future in the mountains

In the HKH, while the spirit of entrepreneurship is strong, the efforts and enablers are scattered. It is necessary to bring them all together – from government, academia, civil society, and the private sector, and to give the new generation the support and opportunities they need.

While drawing on these valuable lessons from the Netherlands, it is essential to contextualise the entrepreneurship approach to mountain specificities. Despite the challenges in the region, there is an upcoming generation of entrepreneurs who are dedicated to applying new social and ecological rules to build successful businesses that have a positive impact on society and nature. They would need a better enabling environment to be successful and to create a long-term impact. With the right kind of support, the youth can play a huge part in shaping the world we want by 2030 – a greener and more inclusive world.

-1758271497.jpg)