Multilateral trade rules under the World Trade Organisation (WTO) were framed to provide a level playing field in the conduct of global investment and trade regimes.

The rule-based trading system has been instrumental in creating jobs, increasing production, and income in many countries, particularly in the global South. Within three decades of the WTO’s existence, countries like China, India, Brazil, Indonesia and Vietnam have made substantial economic progress and lifted millions of their population from absolute poverty.

The global trade rules facilitated the production of goods and services of comparative and competitive advantages, as the conventional market access barriers were reduced to a large extent.

However, the second presidential term of Donald Trump early this year is signalling an upended global economic and financial order under the rubric of ‘Make America Great Again’ as US tariffs are being weaponised to penalise its trade partners. This is undermining the fundamentals of global trade, espoused by the United States in the aftermath of World War II.

The production of goods and services and increasing their productivity lies at the heart of international trade. The economic history of the planet reveals that people have gradually evolved from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age with a shift to agricultural production to improve their living. This was followed by the production of essential goods, including cotton and textiles, considered essential for human beings. This gave rise to manufacturing activities. Over time, manufacturing activities were expanded and diversified, which became a source of employment for an increasing number of people.

With the mechanisation and automation of the industries during the first industrial revolution, the western countries were able to increase huge surpluses of goods that were exported to the third world and their colonial countries.

The second progression in industrialisation took place during the 19th century with the application of electric power, followed by automation, and the third wave was propelled by the use of information technology which took place during the second half of the 20th century.

The fourth wave of industrialisation, started during the beginning of the 21st century, is supported by the internet, big data, artificial intelligence and robotics. Now, industries around the globe are competing to achieve efficiency in their production processes and become cost-effective with the optimum use of new technologies.

Nepal is a latecomer in bringing manufacturing industries into the country which dates back to the 1930s during the reign of Juddha Shumsher. Manufacturing industries such as Biratnagar Jute Mills, Juddha Match Factory, Morang Cotton Mills, and Raghupati Jute Mills were established during the 1930s and 40s. Altogether 63 industries were registered over 14 years between 1936 and 1950.

The establishment of Udyog Parishad (Industrial Council) in 1935, the enactment of the Company Act, the Nepal Patent, Design, and Trade Mark Act, and the establishment of Nepal Bank Limited in 1936 provided the legal and institutional foundations for industrialisation in the country.

From a closed economy, Nepal started liberalising its economy in 1980. The Sixth Plan (1980-85) and the Industrial Policy-1981 recognised foreign direct investment as a crucial element to enhance industrialisation in the country.

With the restoration of multi-party democracy in the country, the pace of economic liberalisation gathered momentum. As part of the reform process, Nepal enacted the Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act and Industrial Enterprises Act and brought out the One Window Policy in 1992. Similarly, the Privatisation Act was passed in 1994, which guided the principles and processes of privatisation of government enterprises. All these efforts were considered to be crucial to funnel domestic and foreign private capital in the industrial establishments in the country.

However, the efforts made in the liberalisation of the economy could not result in the substantial growth of foreign direct investment in Nepal. The total FDI stock in the country stood at Rs 295 5 billion or around $2.1 billion by mid-2023, and investment is mostly centred around hydro-energy, tourism and services.

The manufacturing sector, which is considered crucial from the perspective of employment and export, has not received adequate attention for investment. The overall performance of foreign direct investment seems bleak as the UNCTAD World Investment Report-2024 reveals that Nepal is on the low ebb among the FDI-receiving countries in South Asia. According to the report, Nepal received merely $74 million in 2023, which is much lower compared to countries like Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives, let alone the highest receiving country, India.

The low performance of the industrial sector is induced by a host of factors that include: inadequacy of industrial, transport, and trade-related infrastructure, difficulty in getting access to finance, lack of raw materials for industries, market access barriers and uncertainties, and poor legal support and enforcement of intellectual property rights. The unsteady policy environment, complexities of administrative procedures, delays, and corruption in the regulatory systems have also deterred investors from taking up new projects.

The Government of Nepal stepped in by developing industrial estates in 1963 with the establishment of Balaju Industrial Estate, followed by the development of another 10 estates in the later years. The project for the development of Special Economic Zones was taken up in 2000, and the government announced a plan to establish one large-sized industrial estate in each province, a few years back. But the progress made in the development of these infrastructure is not satisfactory. The regulatory regime to operate the industrial zones and SEZ is restrictive rather than facilitating private investment.

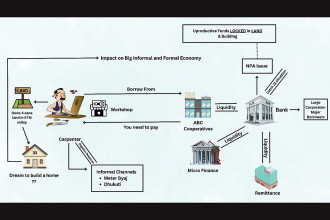

Availability of credit facilities for industries encompasses a winding process that requires collateral of fixed property, like land and house. That scenario frequently proves to be a significant hurdle for smaller industries. These enterprises often face the challenge of securing loans at elevated interest rates, unlike the more favourable terms associated with hire purchase agreements and home loans. Furthermore, they may struggle to furnish the necessary collateral demanded by financial institutions.

Nepal also lacks the supply of raw materials for manufacturing industries. The established industries like edible oil, apparel and garments, carpet, etc., get their raw materials from outside the country. Little attention has been paid to the sustainable use of native resources like minerals, forests and agricultural products. Also, the increasing outflow of young people from the country has not only created shortages of human resources for the industries but has also become a reason for family fissures, exacerbating the social problems.

Nepal’s legal regime on intellectual property rights is not fully compatible with the international trade rules. The Patent, Design, and Trade Mark Registration Act-1965 is still a work in progress, which needs comprehensive review and revision in the light of making it compatible with the WTO agreements. Similarly, the preferential access available to Nepali products in the international markets is affected due to escalating trade conflicts between large trading partners in recent months. The market uncertainties are further accentuated by the imminent loss of market access opportunity in the aftermath of LDC graduation in 2026 and beyond.

The fundamental departure of economic policies from a closed economy to a liberal and market-based economy was considered the best available option for the healthy growth of the economy and prosperity of the nation. However, the much-hyped expectation of the people was shattered due to rampant corruption, inefficiency and the inability of the governance system to deliver services to its stakeholders.

Optimum use of capital and technologies is an essential element in advancing industrialisation in the country. Government policies talk about high-sounding reform measures but these miserably fail in their implementation. Hence, the Government of Nepal should focus on bringing a strategic shift in the mode of implementation of announced policies and programmes.

The Government of Nepal should acknowledge that stacks of policy announcements without a proper implementation scheme and mechanism in place, and the rhetoric of investment summits will not suffice to bring substantial reform in the investment regime of the country.

-1758271497.jpg)