Building a house can be approached in two ways. You can construct a building with a weak foundation that looks good on the outside or you can work hard to ensure the foundation is strong. The first approach is faster and requires less effort and the house may appear beautiful. However, a magnitude 6.6 earthquake could cause the entire structure to collapse, turning everything to dust in an instant. The second approach, while not always immediately yielding an aesthetically pleasing exterior, results in a strong and safe house.

The recently announced Fiscal and Monetary Policies seem to be focused on building ‘beautiful houses’ with good intentions, especially by addressing issues in the real estate sector and stock market. However, I believe this is the wrong approach, similar to the first one, because it fails to address the fundamental issues necessary for rebuilding the foundation of Nepal’s economy.

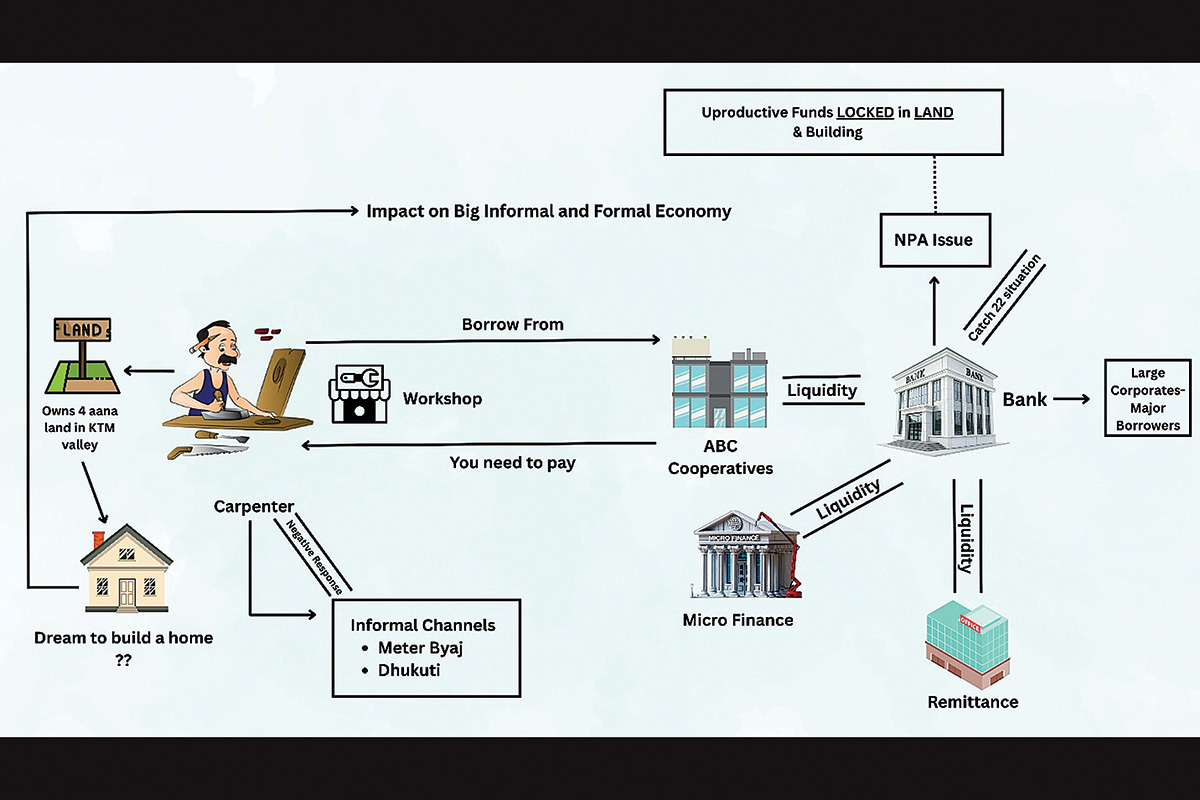

Let’s go through the above diagram step by step:

1. Carpenter’s Story

Consider our example of a carpenter who, five years ago, borrowed Rs seven lakhs from a well-governed financial cooperative to invest in his workshop. He has worked diligently, serving clients and consistently making his principal and interest payments on time, never defaulting.

A couple of years ago, during the annual renewal of his loan, the cooperative’s manager delivered a shocking message: “Sir, this time you must repay all your principal and interest. There is a crisis in the cooperative sector and our depositors are withdrawing their funds. We do not have enough to pay them back, so we need you to repay your loan as soon as possible.” The carpenter was stunned.

“How can I pay all the principal now?” he responded. “As you know, I invested it in infrastructure and machinery for my workshop, which cannot be easily liquidated. I have always paid my installments on time.” His efforts to reason with the manager were in vain, as the cooperative itself was in a financial crisis. This was not due to any wrongdoing on its part but rather to systemic issues stemming from poor governance and flawed regulatory practices prevalent in many other financial cooperatives across the country.

The carpenter’s focus has now shifted from producing quality furniture to repaying his loan. He considers selling his workshop but he lacks the credibility and knowledge of the stringent documentation processes required by Class A or B banks, making a loan from them impossible. Transacting with the financial cooperative was once easy for him but that is no longer an option.

In desperation, he sells his wife’s jewellery, which only raises Rs two lakhs, leaving a large portion of his loan outstanding. He then tries to borrow from the informal ‘Meter-Byazi’ market but this illegal market was shut down by the government a few

years ago.

For someone like the carpenter, his reputation and goodwill are extremely important. As a respected member of his community, he has never cheated or defaulted on a financial transaction. However, this situation has caused him many sleepless nights as he fears being blacklisted by the financial cooperative, which would tarnish his image among his family, relatives and society. He finds himself in ‘dire straits’ through no fault of his own.

2. The Small Micro Enterprise Segment:

The carpentry business in this case study is a prime example of a small micro-enterprise. With approximately 1.5 million such businesses in Nepal, they form the backbone of the country’s economy. These enterprises, which include familiar examples like coffee shops, tailor shops, and bakeries, often employ an average of five people each. This translates to about 7.5 million people in the workforce who are contributing to their own country rather than seeking opportunities abroad.

While the financial transactions of these businesses may not always be captured in official data from organisations like Nepal Rastra Bank or the National Statistics Office, they are the true engine of the economy where significant cash flow occurs. We will explore this analysis further after returning to the case study.

3. Lack of Market Demand – Main problem facing the economy now

The carpenter in our case study, after years of hard work and savings, managed to buy a 4-aana plot of land in a southern Kathmandu suburb. His dream, shared by 99% of Nepalis, is to build a home for his family. However, the current financial crisis makes this dream impossible, placing him in a catch-22 situation. This lack of demand has a cascading effect: the local hardware store, which would sell him cement, steel and other materials, is not getting enough business, leaving its stock idle. As a result, the store owner will not order more supplies from dealers or wholesalers.

This cycle ultimately hurts large manufacturing corporations that produce construction materials, as they are now operating at only 40-50% capacity. Our carpenter’s plight is not unique; like him, millions of business owners face similar issues. This cyclical lack of demand is a major problem for the entire market. Now, let us turn our attention to the formal, large-scale manufacturing factories and the catch-22 situation faced by Class A and B banks.

4. Banks have Excess Liquidity Situation & NPA Problems at the same time

Despite a decrease in lending rates from 13% to 8%, banks are still unable to increase credit due to a lack of quality borrowers. Many traditional borrowers, who used to take out loans for imports and land transactions, are no longer doing so. The government’s decision to restrict imports of non-essential luxury items, coupled with the collapse of the real estate sector, means these sectors are no longer driving loan demand.

Meanwhile, potential new borrowers are hesitant to take on debt. Many businesses are struggling with reduced sales and are more focused on recovering old debts than on expanding. The cyclical effect of the financial crisis has made entrepreneurs cautious, as they see their peers, like our carpenter, unable to build and expand.

This situation has left banks in a difficult position. Despite an influx of deposits and lower lending rates, they cannot find a sufficient number of reliable borrowers. As a result, large sums of money are sitting idle in banks, leading to a surplus of liquidity. This is the catch-22 situation faced by Class A and B banks.

Paradox

Funds have moved to Class A and B Banks but are largely sitting idle, like a still lake, instead of being used for lending to stimulate the economy. Despite borrowing rates dropping as low as 8%, the real sector, particularly construction and real estate, shows little interest in borrowing. This can be explained by our case study’s carpenter, who is struggling to repay his loans and cannot afford to build a house. This, in turn, creates a ripple effect, reducing demand for construction materials from local hardware stores and causing a significant slowdown.

As a result, bank relationship managers are now approaching large corporations that manufacture or trade in construction materials, like cement, steel and aluminium, to offer them low-cost funds. A typical conversation goes like this: a bank’s relationship manager offers a low interest rate of under 8% to a business owner. The owner replies that even a 5% rate is useless when their warehouses are full of two months’ worth of stock and their plants are operating at 40-50% capacity. Without a significant increase in local demand, they cannot justify borrowing more.

This leaves the banks with a major problem. With more and more liquidity they cannot mobilise, they face a substantial negative interest margin pressure on their balance sheets. On top of that, banks are dealing with an increase in non-performing loans from small micro-enterprises they lent to in the past, pushing the sector’s overall non-performing loan ratio above 5%. This makes banks reluctant to lend to this segment. This is the catch-22 situation big banks now face, as they do not

have a business model to work around it.

5. Lesson

Ignoring the growth of 1.5 million small businesses, which employ an estimated 7.5 million Nepalis, makes it impossible to achieve overall economic growth by focusing only on the formal sector. To truly stimulate the economy, we must look beyond official data, the formal corporate sector, and the traditional borrowers of Class A and B banks.

6. Way out

As the title of this article suggests, the government’s intentions, including those of the Ministry of Finance and Nepal Rastra Bank, appear positive, but their approach is too shallow. Implementing measures like increasing housing loan thresholds and enhancing limits for stock market transactions through fiscal and monetary policies will not provide a real solution for the economy.

The solution is complex and challenging but it will be rewarding if tackled with commitment, hard work and the right approach. We need to focus our efforts on the real problem: the situation faced by our carpenter and the 1.5 million other business owners like him.

-1758271497.jpg)