Across the world, governments are locked in relentless competition to achieve higher economic growth, ensure equity and deliver prosperity to their people. Increasing production and productivity, staying competitive, and integrating goods and services into global markets dominate policy priorities. Yet the social and environmental costs of this race – labour exploitation, ecological degradation and climate vulnerability – are routinely sidelined. This growth model is increasingly proving to be both unsustainable and unjust.

The idea of sustainable development entered global discourse in the 1970s, notably at the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm which formally linked development with environmental protection and led to the establishment of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). This linkage gained renewed momentum in 1992 with the Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 adopted at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), alongside landmark conventions such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

Today, the consequences of ignoring those early warnings are unmistakable. Intensifying wildfires in California, floods and landslides in South Asia and Africa, and devastating hurricanes in the Caribbean have caused immense loss of life, property and livelihoods. These climate-induced disasters have also disrupted agricultural production, threatening food security and global supply chains.

Nepal, despite its negligible contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, is among the countries most exposed to climate risks. Rising temperatures are accelerating glacial melt in the

Himalayas, pushing snowlines upward and increasing the risk of glacial lake outburst floods. Events such as the Seti River disaster in 2012 and the Trishuli River surge in 2025 highlight the growing vulnerability. Erratic rainfall patterns have compounded these risks. Intense downpours in September 2024 caused widespread destruction along river corridors in Kathmandu Valley, while recurring heat waves in the Terai continue to undermine agricultural productivity.

Climate change is already affecting Nepal’s food systems, drinking water sources, irrigation, hydropower generation and biodiversity. Yet, the country lacks the technical capacity and financial resources required to effectively adapt to these challenges. This asymmetry – between responsibility and impact – lies at the heart of the global climate injustice.

To its credit, Nepal has long recognised the importance of sustainable development. As early as the Eighth Plan (1992–97), the country committed to balancing agricultural development with environmental protection. The current Sixteenth Plan (2024–29) builds on this foundation by prioritising biodiversity conservation, green economic growth and climate resilience. Ambitious targets include increasing the forest sector’s contribution to GDP from 3% to 5%, raising climate-responsive budgeting from 6% to 20%, enhancing forest density and significantly expanding carbon sequestration through renewable energy and forest management. Community forestry initiatives have already helped increase forest cover to about 45%.

However, national efforts alone are insufficient in the absence of robust global cooperation. Nepal has received limited support from international mechanisms such as the Green Climate Fund, primarily for adaptation measures. While a USD 45 million agreement with the World Bank under carbon trading initiatives offers some relief, uncertainty over long-term international commitment remains a serious concern.

This concern has been amplified by shifting political narratives in developed countries. The withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement and its disengagement from key international climate and renewable energy institutions undermine collective global action. Such decisions disregard the lived realities of billions of people facing intensified climate risks – food insecurity, biodiversity loss, extreme weather events and rising economic costs.

At this critical juncture, developed countries – particularly those with the highest historical responsibility for ecological damage – must demonstrate leadership. Supporting adaptation and resilience in least developed and climate-vulnerable countries is not charity; it is a matter of global responsibility and shared survival.

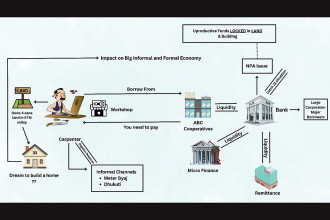

For Nepal, green growth must translate into concrete, livelihood-centred strategies. Priority should be given to the cultivation, processing and sustainable use of non-timber forest products to generate rural employment and export income. Private forestry and sustainable hardwood production should be promoted, with appropriate recognition of forests as productive economic assets supporting manufacturing industries.

At the same time, the transition to clean energy must accelerate. Incentives for electric vehicles, wider adoption of electric appliances, and large-scale investment in renewable energy – initiated decades ago but still underdeveloped – are essential. Expanding access to clean energy in rural and remote areas can reduce fossil fuel dependence, create local jobs and improve living standards.

Green growth is not a luxury for Nepal; it is a necessity. But its success depends as much on global solidarity as on national commitment. Without equitable international cooperation, the promise of sustainable development risks remaining an aspiration rather than a lived reality.

-1758271497.jpg)