Events in the weeks since September have heightened anxieties over renewed great power rivalry, new waves of militarisation, fraying alliances and a resurgent arms race – all centred in the Asia-Pacific region.

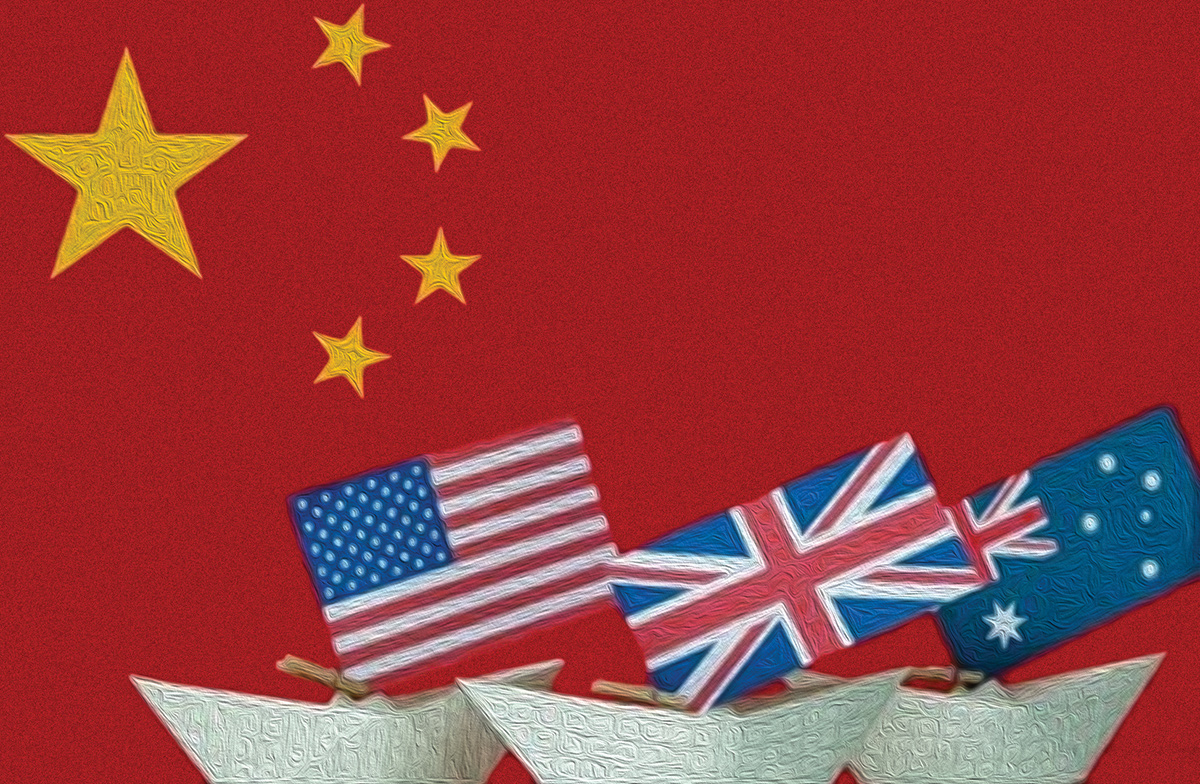

On September 15, the US, Britain and Australia announced AUKUS, a trilateral security pact ostensibly meant to counter Chinese influence in the Indo Pacific. Under the deal, Australia will acquire at least eight nuclear powered submarines from the US. The unspoken but alleged objective: building a strike capacity to demolish China’s naval fleet within 72 hours.

France was quick to raise a ruckus over AUKUS and quite understandably so. The deal cut the French out of a $60 billion contract signed in 2016 to supply 12 Attack-class submarines in replacement of Australia’s ageing fleet. Beyond the economic losses, France claimed it received notice of the snap cancellation a mere couple of hours before AUKUS was publicly announced – “a stab in the back”, according to the French Foreign Minister. In response, a furious France recalled its Ambassador in Washington DC and warned Australia to expect “more than delays” in concluding a Free Trade Agreement with the EU. For now, key EU member-states stand in solidarity with France, with Germany describing the episode as “a wake-up call”. French opposition politicians, meanwhile, have gone as far as to demand that France withdraw from the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the post-World War II political and security alliance between the US and Europe.

In his first address to the United Nations on September 21, US President Joe Biden was expected to signal a big-time US return to the world stage. Rather, he glossed over recent strategic missteps that are still churning in the news cycle – most notably the US surrender to the Taliban and its ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan – and attempted instead to repurpose a Cold War-ish zero-sum binary of “us” versus “them”; of “partners and allies” saving the world from an unnamed evil adversary. But much of the tone that Biden sought to strike rung hollow in the absence of any reference to the many fires burning in his own backyard.

/Almost back-to-back, on September 24, Biden convened an in-person meeting at the White House of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or QUAD, a self-styled “democratic bulwark” against China composed of the US, India, Japan and Australia, concerned primarily with maritime security in the disputed shipping lanes of the South China Sea. The QUAD mission is still evolving 14 years since it was first formed in 2007. In the public mind, its objectives vary quite widely between the likes of a loose talk-shop devoted to sharing grievances against China to an emerging Asian NATO militarily encircling China. Early critics of the initiative described the QUAD as a new Great Game intended to replace the Asian Century with an American Century in Asia.

It’s not like China is taking all of this lying down. Multiple sources report that Beijing successfully tested an intercontinental nuclear-capable hypersonic missile in August, outwitting US military intelligence. True to its penchant for maintaining “strategic ambiguity” when it comes to military matters China has since robustly downplayed the reports, claiming instead that the test was part of a routine space mission. However, if true, this would mark a huge advance in China’s military modernisation and jeopardise the $400 billion that the US has invested in missile technology in the last ten years. For example, hypersonic Chinese missiles could conceivably travel up to five times the speed of sound with a manoeuvrability to evade existing defence systems, including those deployed by the US. Moreover, China is not bound by any international arms-controls agreement that would restrict production and deployment.

Australians appear politically primed to believe that war in the Pacific is imminent much like it was during the earliest days of World War II. Only this time the aggressor will be China and not Japan. They seem so convinced of this inevitability that they see no problem in burning bridges with their largest two-way trading partner, China, accounting for a third of the country’s global total and valued at $250 billion in 2020 before relations began to sour.On October 1, China’s National Day, Beijing authorised 38 of its fighter jets and bombers to intrude into Taiwan’s air defence buffer prompting frantic military alerts and strong US condemnation. Nonetheless, China flew another 111 sorties past the renegade island over the following three days, an all-time record. Then, on October 19, China and Russia conducted joint naval exercises in the Tsugaru Strait, international waters that separate the Sea of Japan from the Pacific – obviously too close to comfort for Tokyo, plagued as it is by longstanding territorial disputes in the region with both China and Russia. Finally, on October 19, North Korea, a staunch Beijing ally, reportedly tested an advanced submarine-launched ballistic missile in violation of UN prohibitions. If confirmed, these new missiles will pose a far greater threat in terms of detection, proximity and payload to Japan and South Korea, both close US allies. It will be many years before Australia receives its fleet of nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS deal. If all goes well, the first ones are slated for delivery only just before 2040, in 19 years’ time. In the meantime, AUKUS must overcome many potential challenges, the most obvious ones relating to compliance with nuclear non-proliferation to which Australia, as of now, is not a signatory. Russia, for one, has a vested interest to see Australia fail this test for this will set a precedent for it to sell its own nuclear-powered submarines to a hungry international market. Australians appear politically primed to believe that war in the Pacific is imminent much like it was during the earliest days of World War II. Only this time the aggressor will be China and not Japan. They seem so convinced of this inevitability that they see no problem in burning bridges with their largest two-way trading partner, China, accounting for a third of the country’s global total and valued at $250 billion in 2020 before relations began to sour. No doubt China, too, is responsible for the escalation in mistrust ever since it over-reacted with stiff sanctions to Canberra’s practical advice that Beijing cooperate with international experts to establish the origins of the Covid 19 virus. Australians are only too familiar with the costs of complacency. They suffered three military shocks in the course of only 71 days in 1941-42 when Winston Churchill refused to defend the former British penal colony against a potential Japanese invasion. This betrayal lives on in infamy in many Australian minds. It eventually took General McArthur and thousands of US troops to prevent the Japanese from landing on Australian shores. Little surprise then that AUKUS involves more than just submarines. It entails US sales worth many billions more in long-range guided missile systems, joint investments in cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies and additional undersea capabilities – all intended to contain China’s economic, military and technological might. And all designed for the US to profit from Australian insecurities. It’s a similar story with Taiwan. A war with China over Taiwan is highly inconceivable even if push comes to shove. But it profits the US war machine to keep up appearances. The former Trump administration sold Taiwan $5 billion in US arms. The Biden administration intends to top that up by another $7 billion. Meanwhile, it suits Taiwan to associate itself with any coalition against China for that brings it closer to attaining the independent, sovereign legitimacy it so desperately craves. At the UN, Biden presented himself as the first US president at peace with the world in 20 years. But most US wars today are fought surreptitiously without a single pair of boots ever hitting the ground. Whether such wars can actually be won is a different matter. Yet clearly, a war with China cannot be won by “over-the-horizon” means. So, Biden maintains he will collaborate with China where he can; compete where he should; and confront where he must. One small problem: China does not entertain such distinctions and disengages at the first sign of hostility - period. As much was evident when Beijing recently snubbed John Kerry, Biden’s Climate Czar. The real risk lies in whether all this hoopla over the China bogey will rob Greater Asia of its economic potentials. As the AUKUS anglophones keep trying to slow China down, in the process they will only end up strengthening Han ethno-nationalism. And China has plans too. With Iran now having joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation as a full member and Afghanistan likely to enter Beijing’s fold, the South China Sea route to westward trade and connectivity will probably lose much of its appeal as China pivots closer to Eurasia over more efficient land routes to Central Asia and on to Europe. General Charles de Gaulle, the French Resistance leader and later President of France, once remarked, “Treaties are like roses…they last till they do.” As such, it will take more than just treaties and military alliances to hold back China.

Published Date: November 15, 2021, 12:00 am

Post Comment

E-Magazine