Fred McMahon

Resident Fellow, Fraser Institute

Fred McMahon is an important voice in global economics. He works as a Resident Fellow and holds the Dr Michael A Walker Chair in Economic Freedom at the Fraser Institute. McMahon has a Master’s degree in Economics from McGill University. His work focuses on development, trade, governance and how economies are structured.

McMahon leads the Economic Freedom of the World Project, which ranks nations based on their economic freedom. He also coordinates the Economic Freedom Network, a global group of over 100 think tanks. He has written many articles and books, including ‘Looking the Gift Horse in the Mouth’ and ‘Road to Growth: How Lagging Economies Become

Prosperous’. His writings often appear in major publications like the Wall Street Journal and Time.

He consistently argues that economic freedom helps countries become prosperous. McMahon’s insights help us understand economic policies in different nations, especially those still developing. Business 360 met with him in Kathmandu to discuss economic freedom and other key issues for Nepal’s economy. Excerpts:

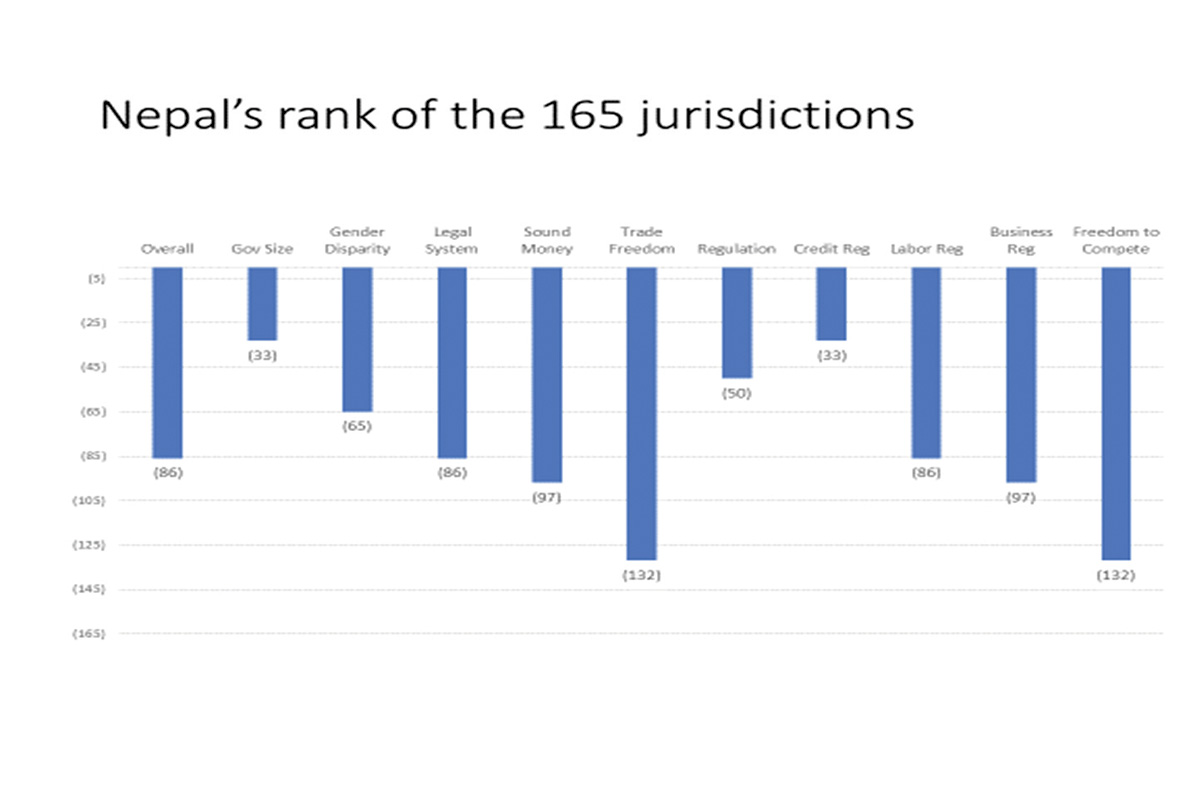

Your work emphasises the importance of economic freedom in fostering prosperity. Where does Nepal stand in the Economic Freedom of the World Index, and what specific areas should Nepal focus on to improve its score?

We measure economic freedom with 43 variables in five areas: Size of government, legal system, sound money (mostly variables on the stability of money value), freedom to trade, and regulation in credit, labour and business markets, and regulations reducing freedom to compete.

The chart below shows Nepal’s rank out of the 165 jurisdictions we measure. Nepal is in the bottom half overall and in legal system.

Creating an impartial and timely legal system, one that Nepalis and foreign businesses can trust, would create a huge economic boost. Businesses crave certainty as an investment today will only pay off years in future. Lack of trustworthy legal systems creates immense uncertainty since no one knows what it will decide and why.

Opening Nepal to world trade would also be a great boost. Trade is a powerful growth booster for a developing nation. Nepal needs the eight billion people in the world as its market, not just its 30 million population.

Nepal has a poor score in freedom to compete which is the engine of economic growth. Without competition, businesses do not have to do much to maintain their market. Growth withers since firms do not need to compete to improve. With competition, they have to constantly improve products and productivity or the competition will eat their lunch. This drives productivity growth which drives increased prosperity. Productivity increase is the engine of prosperity.

Barriers to freedom to compete are reinforced by Nepal’s low rank on business regulation, meaning unnecessary regulation. Restrictions on business increase the difficulty of creating ways to improve productivity.

Nepal has a low score and rank on freedom to trade. This piles on other barriers to competition. To produce high levels of prosperity, Nepal needs to compete with the world. Shutting out the world means Nepali companies never face the competition that generates gains in productivity.

You have written about the ‘negative sum economy’ in some regions. Do you see similar risks for Nepal if it continues to depend on aid, remittance and limited private-sector growth?

The problem I discussed was the attitude that any loss of an existing business is a dead loss and will never be replaced. This leads to policies that protect or subsidise existing businesses whether they are competitive or not. This ‘negative sum attitude’ freezes out new and innovative businesses by putting up barriers and protecting old and inefficient one. So yes, without more productive businesses in Nepal, Nepalis will continue to leave the country sending back remittances that serve only to keep the economy afloat and government complacent rather than address the problems in the Nepali economy.

How can Nepal leverage its geographic position, being in-between two giant economies, to improve trade and attract investment while maintaining its economic sovereignty?

Nepal lacks good trade routes to China with particularly poor infrastructure on the Nepal side. It has fairly good trade routes to India. Nonetheless, improved infrastructure to both nations would help increase trade.

Even more importantly, a competitive economy creating productivity improvements is necessary to increase trade with Indian and China – consumers in both nations are only going to be interested in quality products at competitive prices.

Nonetheless, having two gigantic markets on each side is a great advantage if you build better infrastructure and an economy that generates products and services that markets desire. So, freeing up the economy is a necessary condition. How to keep the good relations on both sides of each is beyond my expertise.

You have studied trade barriers extensively. What are some ‘unseen walls’ that might be limiting Nepal’s global trade potential beyond the obvious infrastructure gaps?

One of the more ironic barriers to exports is not an explicit barrier to exports (there are plenty of these) but the import duties and other barriers to imports. This deprives Nepali businesses of reasonably-priced imported equipment to improve their quality and productivity and of raw materials and intermediate goods needed to produce many exports.

Another barrier to trade is the syndication in the transportation and logistics sector. Due to lack of competition, this leads to higher costs, inefficiency, uncertainty, and delays for Nepali exporters.

Samriddhi Foundation has produced a marvellous report on trade. Let me quote directly from it on another challenge facing trade: “Compliance with non-tariff measures – complex documentation processes, the need for multiple certifications, and lengthy approval processes have been a few problems faced by the traders. The ITC (International Trade Centre) survey reports that around 51% of exporters encounter problematic NTMs, with the agriculture sector being particularly affected. Testing and certification by other government agencies (OGAs) contribute to delays at customs. On average, these agencies, which include quarantine facilities and laboratories, take 19 hours and 46 minutes, accounting for 20% of the total clearance time. Since these agencies are located outside the customs area, and the absence of a single window system for the OGA services delays the procedure of testing samples and the issuance of certificates. Additionally, exporters face the problem of getting approval from the Bureau of Indian Standards, forcing them to rely on Indian labs, which significantly prolongs the process. These problems at the procedural level are largely due to Nepal’s poor quality of national infrastructure.”

Given the Fraser Institute’s work on economic freedom and trade, what lessons can Nepal learn from other landlocked countries that have successfully integrated into global markets?

Being landlocked with difficult geography is a challenge. To overcome this, Nepal needs to have good policy rather than policy that stifles trade adding to the problems of geography.

This is the path taken by nations with similar difficulties that have succeeded. Switzerland faces the same geographic situation but it is usually number three in the economic freedom rankings, the highest ranking of a non-Asian jurisdiction and the highest ranking of a non-micro jurisdiction. (Only Singapore and Hong Kong have higher levels and for obvious reasons Hong Kong’s scores have been declining.)

So, Switzerland with a geography in many ways similar to Nepal has become one of the most prosperous nations on the planet through growth-enhancing economic policy. Like Nepal, it is adjacent to a huge market, Europe, in Nepal’s case India and China.

Other landlocked states that have relatively high levels of economic freedom are also succeeding: Austria and Czechia, for example. Landlocked Botswana has on average been the most economically free nation in sub-Sahara Africa and has had the highest growth rate in the region by far. It has diamond resources but many African states have great resources and failing economies. (Unfortunately, Botswana has been weakening in economic freedom so its success may not endure.)

Bottom line: Nepal, like many other nations, can overcome bad geography by good economic policy.

You often emphasise the role of governance in economic development. In Nepal’s context of federalism and political instability, what are the most critical governance reforms needed to unlock economic growth?

You put it correctly: establishing stability and a trustworthy government is necessary for economic growth. Business cannot invest today if they are unsure what the economic policy will be down the road when their investment will start paying off. However, I am not familiar enough with Nepal’s complicated and confusing political situation to make any specific comments.

How important is the protection of property rights and judicial independence in promoting economic freedom, especially in developing democracies like Nepal?

This is the single most important area of economic freedom. Without a firm, fair and timely rule of law, the rich and the powerful will enrich themselves by limiting the economic freedom of the poor and powerless. Improving the legal system is the work of generations, so each generation must move things forward or Nepal will never be blessed by an appropriate rule of law. Government can order a tax change on Tuesday and pretty much have it in place by Wednesday; but, if on Tuesday, government orders all judges, police, and officials to be honest and competent by Wednesday, little will happen. So, progress is slow but necessary.

Looking at Nepal through the lens of your book Road to Growth, what are some warning signs or bottlenecks that could prevent it from joining the league of prosperous economies?

My home area of Canada, Atlantic Canada, has long been Canada’s poorest region, but in the 1950s and 1960s it was rapidly catching up with the rest of Canada. But then, the federal government decided to boost the region by pouring in billions and billions of dollars to lift growth. The opposite happened and the region’s catch up with the rest of the nation came to a halt.

The way the money was spent created numerous problems including one with similarity to the Nepali remittances. The extra money from Canada’s federal government created a sense of complacency both for business and regional governments, which used the extra money to fund programmes that reduced economic freedom. To some extent, this parallels the effect of huge remittances to Nepal. The government has a cushion to protect it from the effects of bad policy, reducing the drive for better policies. This is a tragedy for Nepalis seeking prosperity for themselves and their families who leave Nepal.

Your work spans decades and many countries. Have you come across any low-income country that reminds you of Nepal’s current situation and if so, how did it change its trajectory?

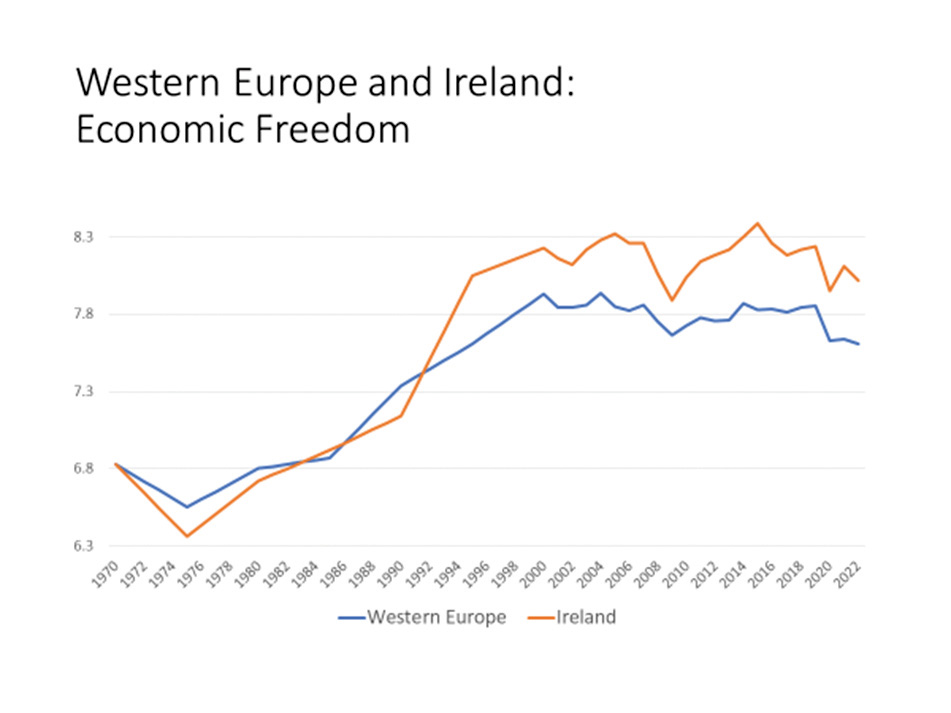

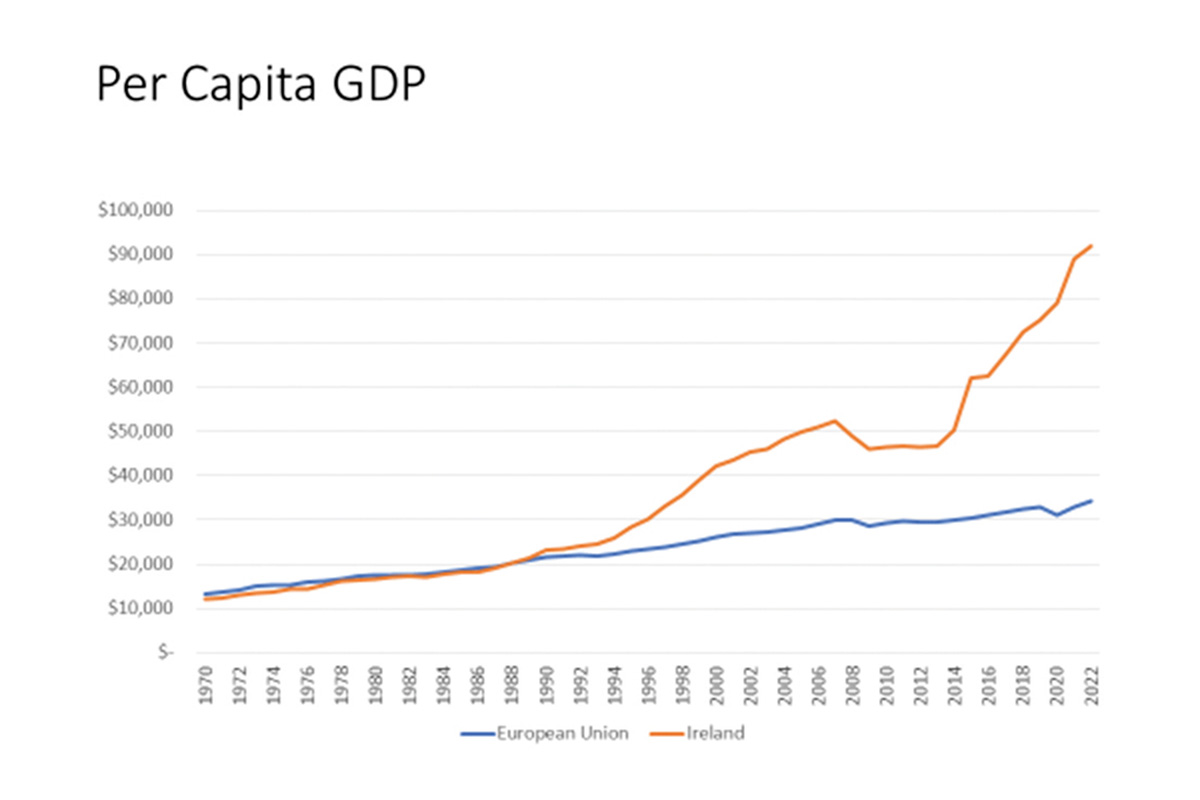

There are no exact parallels but here are some comparisons: Ireland, a relatively small European nation, was long one of the poorest nations in western Europe but in 1987 it launched major economic reforms that raised its economic freedom score from 6.92 in economic freedom in 1985 to 8.05 in 1995. Its economic growth soared. (See charts 1 and 2)

New Zealand saved itself from an economic crisis and launched a period of great growth following similar reforms boosting economic freedom at about the same time as Ireland, raising its score from 6.96 in 1985 to 8.91 in 1995. Again, growth soared.

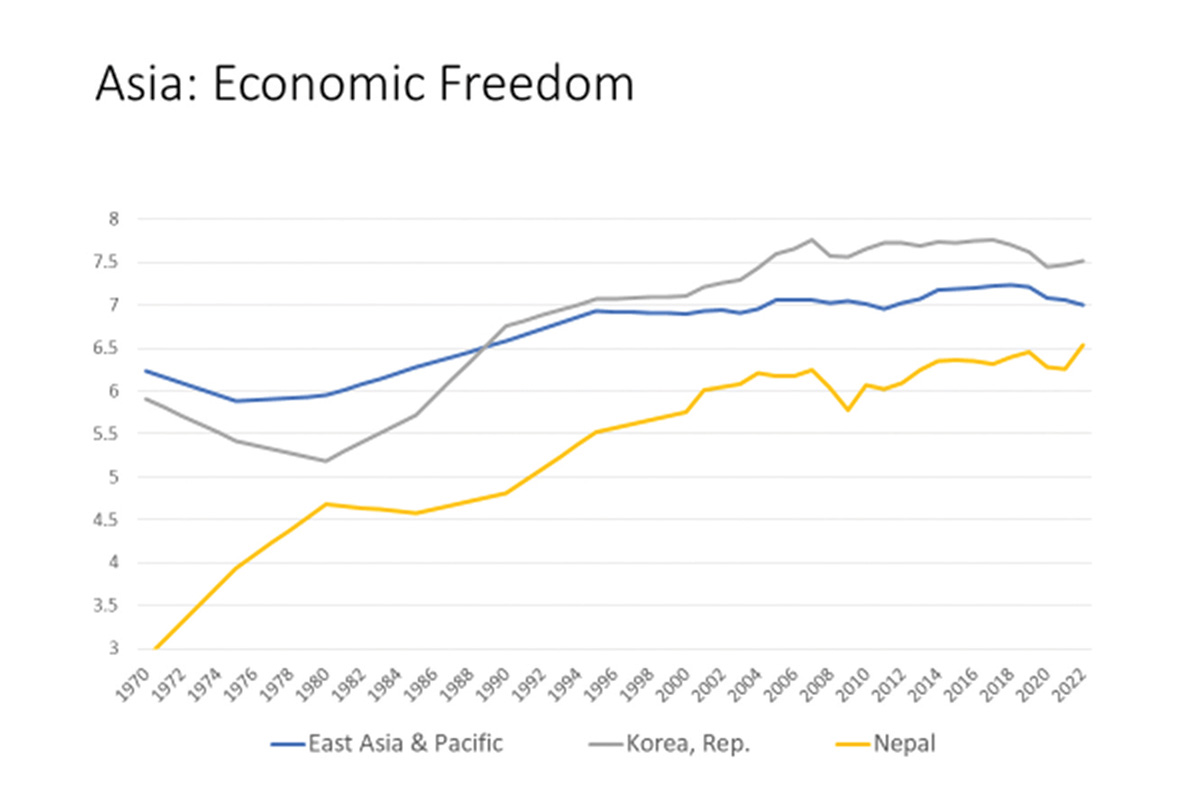

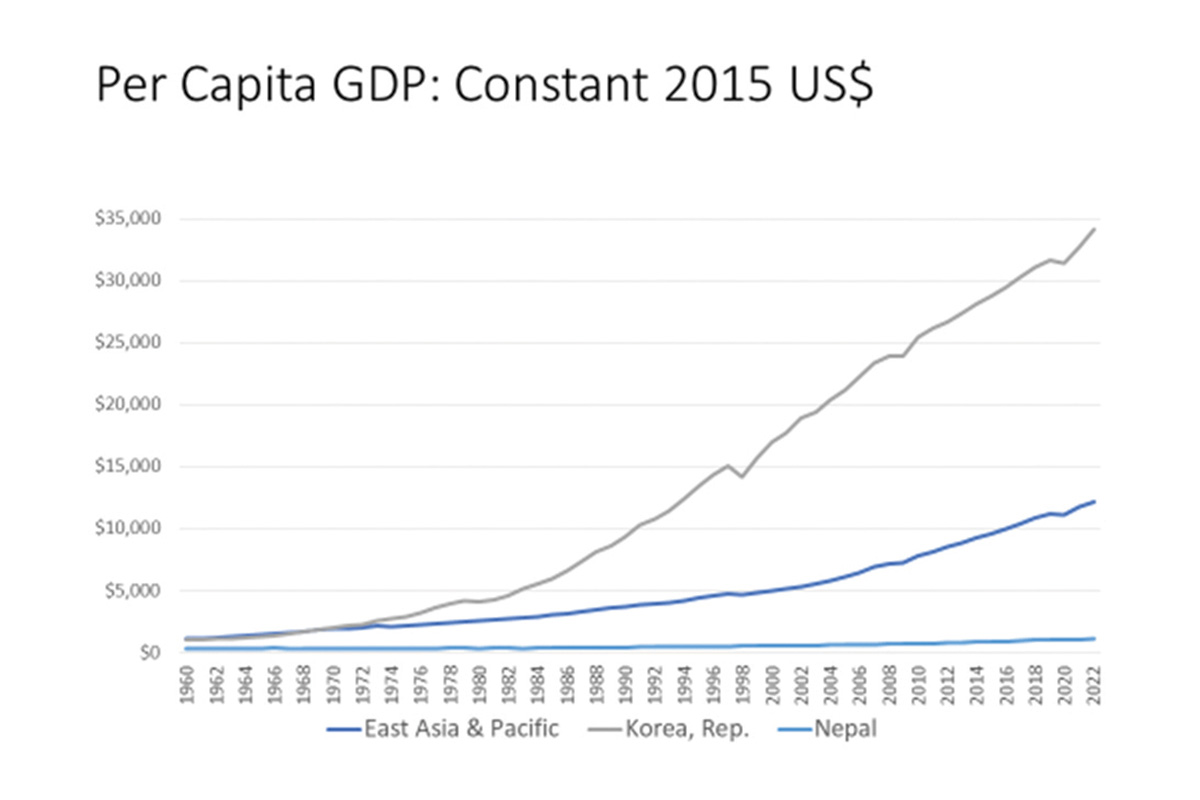

South Korea, once not much more prosperous than Nepal, launched big reforms in the in the early 1980s boosting economic freedom and its growth took off. See charts below which include Nepal. (See charts 3 and 4)

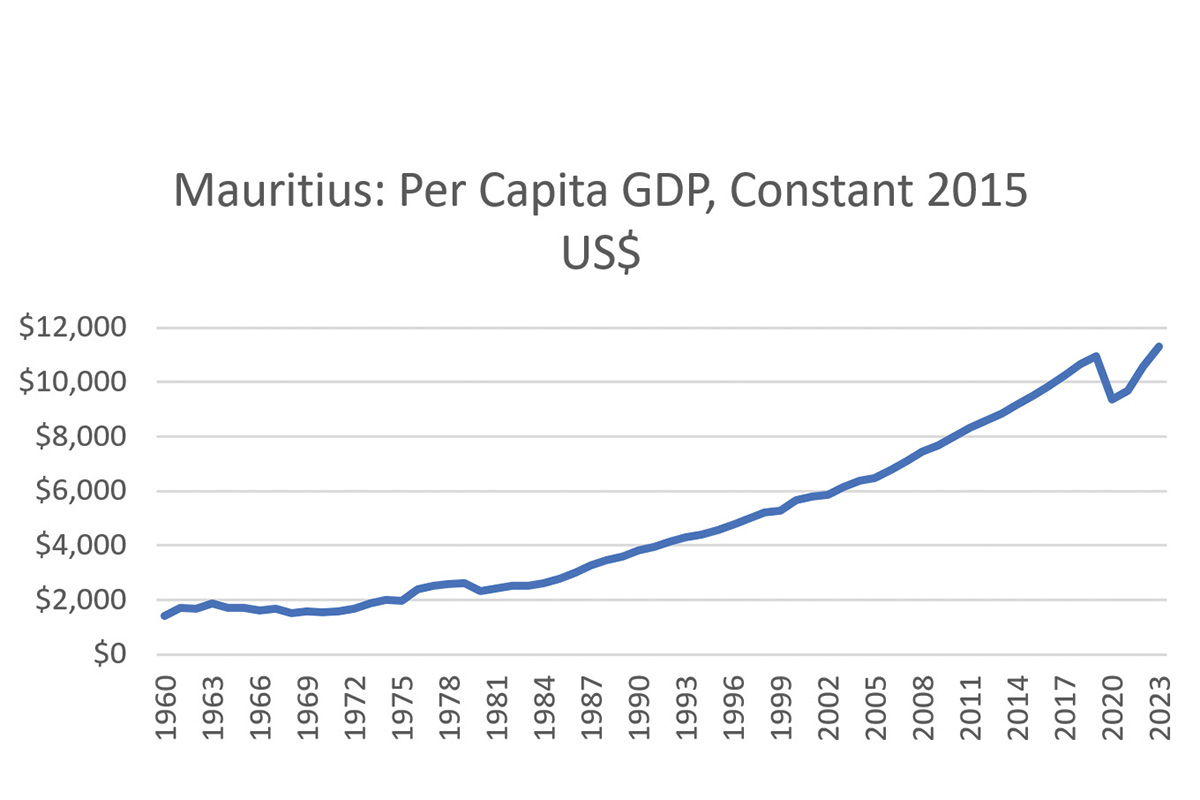

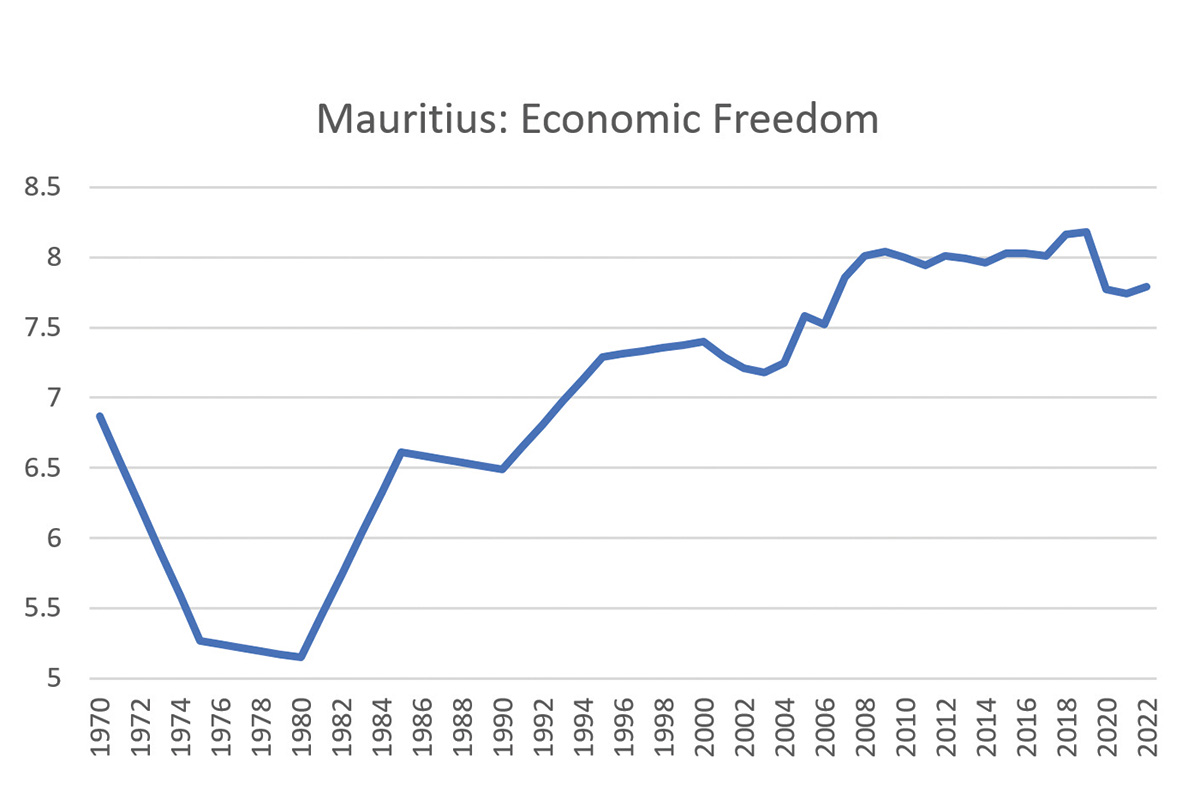

Mauritius has a similar story, economic reform in the early 1980s followed by strong growth. (See charts 5 and 6).